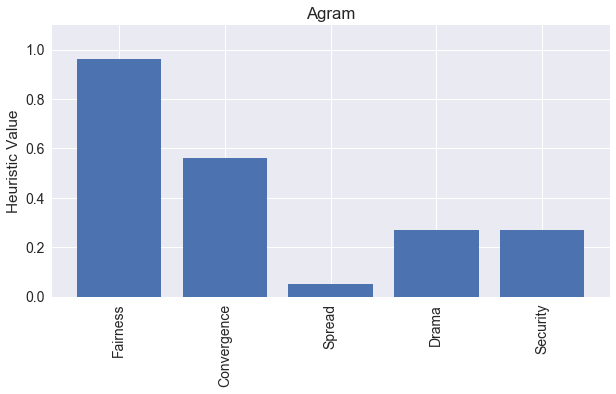

With our heuristics overview complete from the last post, let’s see how Agram scores on Fairness, Convergence, Spread, Drama, and Security. Some of the following graphs should look familiar, as they were used to explain how our heuristics are calculated.

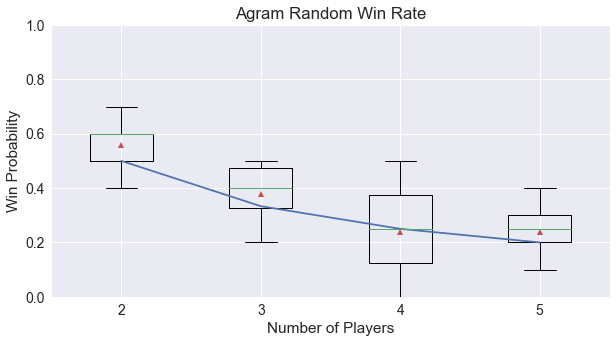

Fairness = 0.96

Agram appears to be a mostly fair game. If we look across all of our experiments for various numbers of random players, this is result is consistent.

In a trick-taking game, there is some advantage to going first in determining the lead suit, but players who go later in turn order always have the opportunity to play higher cards with more certainty in their outcome for winning the trick. Many times, it is the cards dealt rather than the player choices that determine who wins the game.

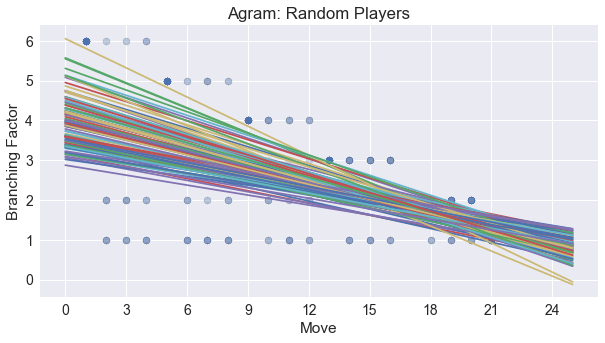

Convergence = 0.56

Agram exhibits convergence toward limited options at the end of the game. We can see a negative slope for each of the regression lines across 100 simulations, calculated for the number of choices a player has in the game in the following graph.

This is consistent for games played with all random players, with one AI player in the mix, and with all AI players. Because of the following players being limited in their options occasionally, the slope is not as steep as it could be.

Spread = 0.05

The spread of choices in Agram is very small. One reason for this is that in Agram, there is only one point awarded in the game, for winning the last trick. This scoring method limits players to be either a first place winner, or a second place loser.

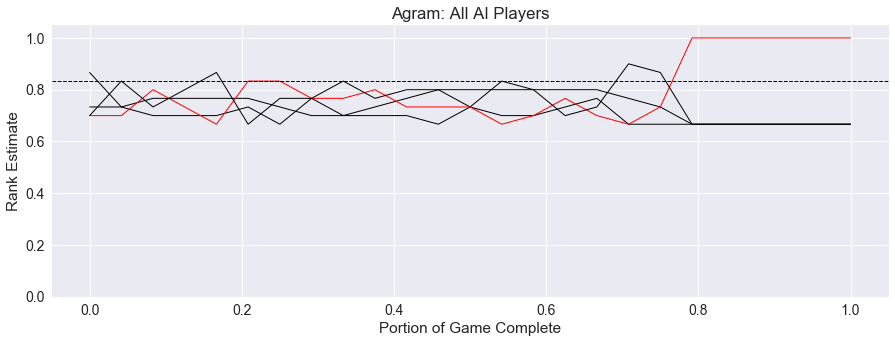

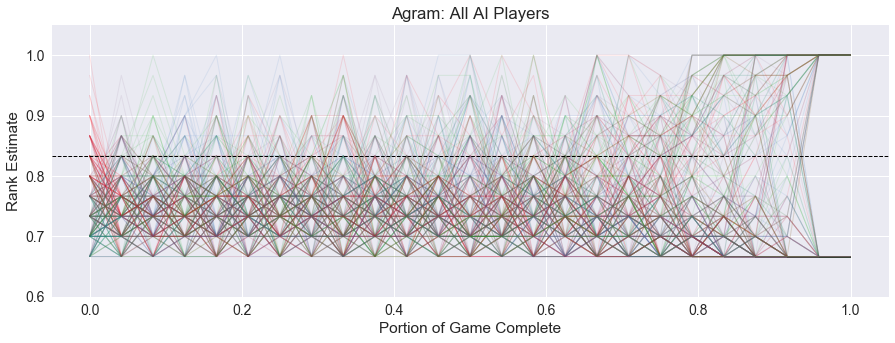

For convenience and to easily compare games with different number of players, the player rank is always scaled to be between 0 and 1, with 1 being the player in first place, and 0 being the player in last place. With four players, this means that the second, third, and fourth place players will be tied at 0.66, as we can see in the following lead history graph.

Because of these compressed values, the spread for the players will be smaller than other games. Also, because the game is undetermined until the last trick, most player’s choices in the beginning of the game look equally unattractive, reducing the spread even further.

Drama = 0.27

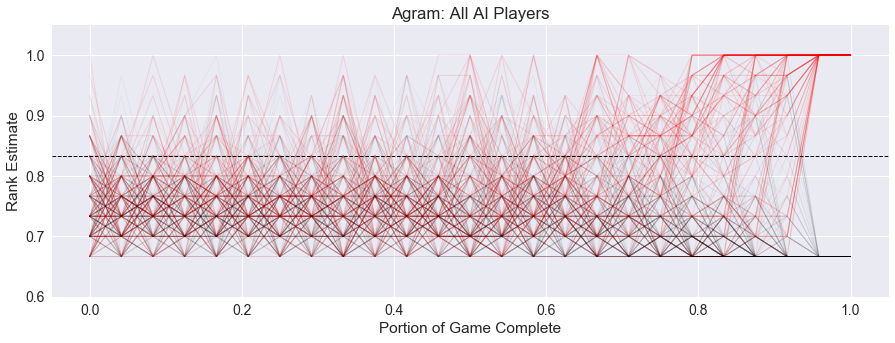

With the winner determined very late in the game, we would expect a higher score for drama in Agram. As we can see in the image above, it is only near the end of the game that the winner, shown in red, can be found consistently above the drama threshold. However, this is again tempered by the limited ranks in the game.

Below, I’ve included an aggregate image of all 100 simulations with all AI players, with the lead histories overlaid. Player 1 is red, player 2 is green, player 3 is cyan, and player 4 is magenta.

One thing to note is the cycle of colors early on for the players. When it is a player’s turn, there appears to be a tendency for them to overestimate their chances of winning, especially in the early part of the game. This is a side-effect of our AI strategy, where it assumes that it is able to make an intelligent choice, but all the other players are playing randomly.

Second, we notice the definite trend that the game is undecided until the second-to-last trick, and pretty much determined in the last trick. This again fits with the game mechanics.

Security = 0.27

Finally, we can visualize the aggregate path of the winning player. The below image shows the same 100 four-player games as above, but with the winning player in red, and all other players in black.

WRONG!!! There are some red peaks early, but especially in the second half of the game, we can see a strong tendency for the winning player to be above the drama threshold, and thus feel secure in their chances of winning the game.

Summary

Here is a graph of all five heuristics for the four-player version of Agram.

In summary, Agram appears to be a fair game. There is some convergence and security present, with moderate drama for the winning player, but not much spread in terms of player choices.

Does this make Agram a good game? Well, that depends on what you are looking for in a game. Also, remember that these heuristics are influenced by our choice of a simple AI; more intelligent players might make different choices and change the shape of the game.

Up Next - Pairs

This series of posts took a little bit longer than I had planned, but I think I now have the pipeline set up to generate all the data and graphs for each new game quickly. Next up, we’ll look at Pairs, a press-your-luck card game for 2 to 6 players, described by designers James Ernest and Paul Peterson as a new classic pub game. Give the rules a read, and we’ll examine the coding, statistics, and heuristics in future posts!

comments powered by Disqus