The standard game of Hearts is coded in RECYCLE, so we can start up our simulations in CardStock with both random and AI players. As before, to gather statistics for this and the next post on heuristics, we ran 100 games with all random players, 100 games with one AI and the rest random players, and 100 games with all AI players.

For Hearts, we did these simulations for 3, 4, and 5 players. To alter the game for 3 players, we removed the 2 of Diamonds, and dealt each player 17 cards. To modify for 5 players, we removed the 2 of Diamonds and 2 of Spades, and dealt each player 10 cards. Let’s see if we can answer some basic questions about the game.

Are there sufficient choices for players?

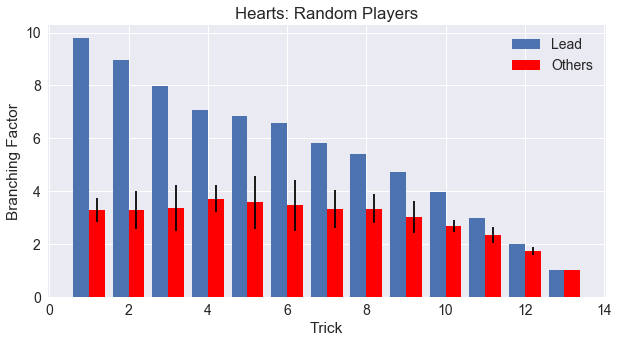

At the most, a player in Hearts will be able to play any card in their hand to the trick. But this is restricted in two ways. First, players that are not the lead player will need to follow suit if possible, and this is a great way for the lead player to limit other player’s choices to their advantage. The following graph for the four-player simulations shows the number of choices for the players in Hearts, with the lead in blue and the other players in red. The other player’s options are averaged into one value, with the standard deviation error bars plotted.

If we think of a hand of cards in Hearts being evenly distributed, we would expect to see on average 3.5 cards of each suit. Of course part of what makes the game interesting is the uneven distribution of these cards and managing the altered probabilities, but this gives us a starting place to examine the graph.

Following suit should then limit the other players to on average 3.5 cards. This is exactly what happens, and it is borne out across the whole round! (Until the last few tricks when players will have less than 3 cards remaining in their hand.) Another point to notice about the other player’s choices is that the standard deviation starts is much larger for tricks 5 and 6. This is due to the players starting to become short-suited and thus having more options for play.

When is Hearts broken?

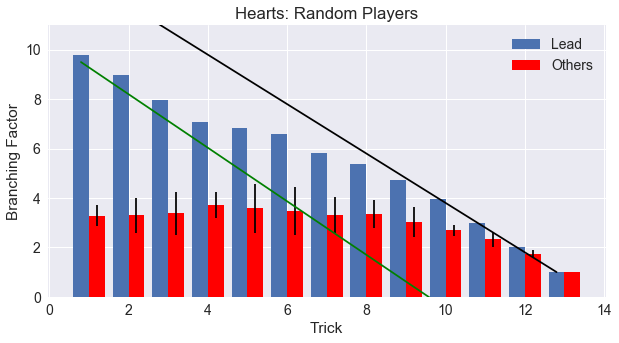

Second, unlike most trick-taking games, the lead player will be restricted to not lead a Heart until one has been played in a previous round by a following player, thus “breaking” Hearts open for play. When does this happen? Interestingly, we also see the same 3.5 cards in one suit effect for the lead player in the above graph. The limitation of Hearts not being broken cuts the average choices for the lead player from 13 to approximately 10 for the first trick, with similar effect for the second, third, and fourth trick. But then, we see a shift happen. In tricks 5 and 6, the lead player choices level off around 7. This must be where Hearts is most likely to be broken! The shift continues for the next few tricks, until trick 10, when the number of lead choices matches exactly the number of cards remaining in the player’s hand.

To make this shift from unbroken to broken Hearts more visually clear, I’ve added two lines in the next graph. The green line shows the expected number of choices for the lead player if Hearts is never broken, while the black line shows the expected number of choices if Hearts are allowed on every trick. We start out following the slope of the green line, and slowly shift to follow the black line as the game progresses.

How does game length vary with the number of players?

The game length of Hearts does depend on the number of players, but the math for this is directly related the division of the card deck. Removing one or two cards makes the total evenly divisible for 3, 4, and 5 players.

Can players be strategic in Hearts?

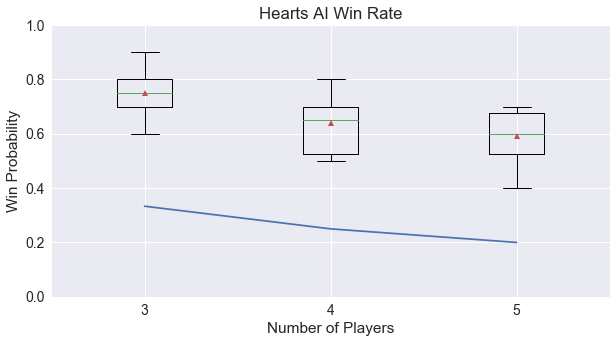

How much of a player’s win can be attributed to luck versus skill in Hearts? The image below shows the win rates of AI players versus random players averaged across the 3, 4, and 5-player games simulated.

It appears that AI players can be successful, and unlike other games, more successful with more players! This is because more players allows for better chances of avoiding the limited number of Hearts cards in the game. Also, in comparison to what we found in our other trick-tacking game Agram, AI players in Hearts are more likely to be able to win the game.

Up Next

It is time to define a heuristic for the above strategic quality of the game, to make it possible to compare differences across games. I’m starting to see that some games are easier for our simple AI players to win over random players than others, and this could be a useful heuristic for clustering games in the future. I’ll make a full post about this new heuristic, then turn to the complete Hearts analysis with lead histories, there are some unexpected scoring results for the AI players I can’t wait to share!

comments powered by Disqus